CCL21

Chemokine (C-C motif) ligand 21 (CCL21) is a small cytokine belonging to the CC chemokine family. This chemokine is also known as 6Ckine (because it has six conserved cysteine residues instead of the four cysteines typical to chemokines), exodus-2, and secondary lymphoid-tissue chemokine (SLC).[5][6][7] CCL21 elicits its effects by binding to a cell surface chemokine receptor known as CCR7.[8] The main function of CCL21 is to guide CCR7 expressing leukocytes to the secondary lymphoid organs, such as lymph nodes and Peyer´s patches.[9]

Gene[edit]

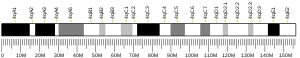

The gene for CCL21 is located on human chromosome 9.[10] CCL21 is classified as a homeostatic chemokine, it is produced constitutively. However, its expression increases during inflammation.[9][11]

Protein structure[edit]

Chemokine CCL21 contains an extended C-terminus which is not found in CCL19, another ligand of CCR7. C-terminal tail is composed of 37 amino acids rich in positively charged residues and therefore, it has high affinity for negatively charged molecules of the extracellular matrix. The cleavage of the C-terminal tail by peptidases produces a soluble form of CCL21.[12] The soluble CCL21 occurs also in physiological conditions. It does not bind to extracellular matrix and therefore, its function differs from the function of the full-length CCL21.[11]

Function[edit]

Migration to secondary lymphoid organs[edit]

Naïve T cells circulate through secondary lymphoid organs until they encounter the antigen.[13] CCL21 is a chemokine involved in the recruitment of T cells into secondary lymphoid organs. It is produced by lymphatic endothelial cells and lymph node stromal cells.[7][12] Full-length CCL21 is bound to glycosaminoglycans, and endothelial cells and it induces the chemotactic migration of T cells and the cell adhesion caused by integrin activation.[9] In contrast, the soluble CCL21 is not involved in the induction of the cell adhesion.[11] After T cells enter the lymph nodes through high endothelial venules, they are attracted to the T cell zone, where fibroblastic reticular cells are the abundant source of CCL21.[13][9]

CCL21/CCR7 interaction also plays a role in the migration of dendritic cells to the secondary lymphoid organs.[14][11][9] Dendritic cells upregulate the expression of CCR7 during their maturation.[14] CCL21 is bound to the lymphatic vessels and attracts CCR7 expressing dendritic cells from peripheral tissues. Then they migrate along the chemokine gradient to the lymph node where they present the antigen to T cells.[9] Interactions between dendritic cells and T cells are necessary for the initiation of the adaptive immune response.[15] When CCL21 is not recognized by the cells (for example in CCR7-deficient mice), a delayed and reduced adaptive immune response occurs due to reduced interactions between dendritic cells and T cells in the lymph nodes.[9] Semi-mature dendritic cells express CCR7 in the absence of a danger signal. They use CCL21 chemokine gradient for the migration to the lymph nodes even when there is no inflammation in the body, and they contribute to peripheral tolerance.[11]

Other cells using chemokine CCL21 for the migration to the lymph nodes are B cells. However, they are less dependent on it in comparison to T cells.[9]

T cell development in the thymus[edit]

CCL21/CCR7 interaction plays a role in the T cell development in the thymus. CCL21 is produced in the thymus medulla by medullary thymic epithelial cells, and it attracts single positive thymocytes from the thymus cortex to the medulla, where they undergo negative selection to delete autoreactive thymocytes.[9]

References[edit]

- ^ a b c GRCh38: Ensembl release 89: ENSG00000137077 – Ensembl, May 2017

- ^ a b c GRCm38: Ensembl release 89: ENSMUSG00000094686 – Ensembl, May 2017

- ^ "Human PubMed Reference:". National Center for Biotechnology Information, U.S. National Library of Medicine.

- ^ "Mouse PubMed Reference:". National Center for Biotechnology Information, U.S. National Library of Medicine.

- ^ Hedrick JA, Zlotnik A (August 1997). "Identification and characterization of a novel beta chemokine containing six conserved cysteines". Journal of Immunology. 159 (4): 1589–1593. doi:10.4049/jimmunol.159.4.1589. PMID 9257816. S2CID 23429282.

- ^ Hromas R, Kim CH, Klemsz M, Krathwohl M, Fife K, Cooper S, et al. (September 1997). "Isolation and characterization of Exodus-2, a novel C-C chemokine with a unique 37-amino acid carboxyl-terminal extension". Journal of Immunology. 159 (6): 2554–2558. doi:10.4049/jimmunol.159.6.2554. PMID 9300671. S2CID 33971251.

- ^ a b Nagira M, Imai T, Hieshima K, Kusuda J, Ridanpää M, Takagi S, et al. (August 1997). "Molecular cloning of a novel human CC chemokine secondary lymphoid-tissue chemokine that is a potent chemoattractant for lymphocytes and mapped to chromosome 9p13". The Journal of Biological Chemistry. 272 (31): 19518–19524. doi:10.1074/jbc.272.31.19518. PMID 9235955.

- ^ Yoshida R, Nagira M, Kitaura M, Imagawa N, Imai T, Yoshie O (March 1998). "Secondary lymphoid-tissue chemokine is a functional ligand for the CC chemokine receptor CCR7". The Journal of Biological Chemistry. 273 (12): 7118–7122. doi:10.1074/jbc.273.12.7118. PMID 9507024.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i Comerford I, Harata-Lee Y, Bunting MD, Gregor C, Kara EE, McColl SR (June 2013). "A myriad of functions and complex regulation of the CCR7/CCL19/CCL21 chemokine axis in the adaptive immune system". Cytokine & Growth Factor Reviews. 24 (3): 269–283. doi:10.1016/j.cytogfr.2013.03.001. PMID 23587803.

- ^ Blanchet X, Langer M, Weber C, Koenen RR, von Hundelshausen P (July 2012). "Touch of chemokines". Frontiers in Immunology. 3: 175. doi:10.3389/fimmu.2012.00175. PMC 3394994. PMID 22807925.

- ^ a b c d e Hauser MA, Legler DF (June 2016). "Common and biased signaling pathways of the chemokine receptor CCR7 elicited by its ligands CCL19 and CCL21 in leukocytes". Journal of Leukocyte Biology. 99 (6): 869–882. doi:10.1189/jlb.2MR0815-380R. PMID 26729814. S2CID 5005741.

- ^ a b Jørgensen AS, Rosenkilde MM, Hjortø GM (March 2018). "Biased signaling of G protein-coupled receptors - From a chemokine receptor CCR7 perspective". General and Comparative Endocrinology. 258: 4–14. doi:10.1016/j.ygcen.2017.07.004. PMID 28694053.

- ^ a b Hunter MC, Teijeira A, Halin C (December 2016). "T Cell Trafficking through Lymphatic Vessels". Frontiers in Immunology. 7: 613. doi:10.3389/fimmu.2016.00613. PMC 5174098. PMID 28066423.

- ^ a b Förster R, Davalos-Misslitz AC, Rot A (May 2008). "CCR7 and its ligands: balancing immunity and tolerance". Nature Reviews. Immunology. 8 (5): 362–371. doi:10.1038/nri2297. PMID 18379575. S2CID 19725359.

- ^ Bousso P (September 2008). "T-cell activation by dendritic cells in the lymph node: lessons from the movies". Nature Reviews. Immunology. 8 (9): 675–684. doi:10.1038/nri2379. PMID 19172690. S2CID 6551798.

External links[edit]

- Human CCL21 genome location and CCL21 gene details page in the UCSC Genome Browser.

Further reading[edit]

- Nagira M, Imai T, Hieshima K, Kusuda J, Ridanpää M, Takagi S, et al. (August 1997). "Molecular cloning of a novel human CC chemokine secondary lymphoid-tissue chemokine that is a potent chemoattractant for lymphocytes and mapped to chromosome 9p13". The Journal of Biological Chemistry. 272 (31): 19518–19524. doi:10.1074/jbc.272.31.19518. PMID 9235955.

- Hedrick JA, Zlotnik A (August 1997). "Identification and characterization of a novel beta chemokine containing six conserved cysteines". Journal of Immunology. 159 (4): 1589–1593. doi:10.4049/jimmunol.159.4.1589. PMID 9257816. S2CID 23429282.

- Hromas R, Kim CH, Klemsz M, Krathwohl M, Fife K, Cooper S, et al. (September 1997). "Isolation and characterization of Exodus-2, a novel C-C chemokine with a unique 37-amino acid carboxyl-terminal extension". Journal of Immunology. 159 (6): 2554–2558. doi:10.4049/jimmunol.159.6.2554. PMID 9300671. S2CID 33971251.

- Gunn MD, Tangemann K, Tam C, Cyster JG, Rosen SD, Williams LT (January 1998). "A chemokine expressed in lymphoid high endothelial venules promotes the adhesion and chemotaxis of naive T lymphocytes". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 95 (1): 258–263. Bibcode:1998PNAS...95..258G. doi:10.1073/pnas.95.1.258. PMC 18193. PMID 9419363.

- Yoshida R, Nagira M, Kitaura M, Imagawa N, Imai T, Yoshie O (March 1998). "Secondary lymphoid-tissue chemokine is a functional ligand for the CC chemokine receptor CCR7". The Journal of Biological Chemistry. 273 (12): 7118–7122. doi:10.1074/jbc.273.12.7118. PMID 9507024.

- Campbell JJ, Bowman EP, Murphy K, Youngman KR, Siani MA, Thompson DA, et al. (May 1998). "6-C-kine (SLC), a lymphocyte adhesion-triggering chemokine expressed by high endothelium, is an agonist for the MIP-3beta receptor CCR7". The Journal of Cell Biology. 141 (4): 1053–1059. doi:10.1083/jcb.141.4.1053. PMC 2132769. PMID 9585422.

- Jenh CH, Cox MA, Kaminski H, Zhang M, Byrnes H, Fine J, et al. (April 1999). "Cutting edge: species specificity of the CC chemokine 6Ckine signaling through the CXC chemokine receptor CXCR3: human 6Ckine is not a ligand for the human or mouse CXCR3 receptors". Journal of Immunology. 162 (7): 3765–3769. doi:10.4049/jimmunol.162.7.3765. PMID 10201891. S2CID 23946439.

- Gosling J, Dairaghi DJ, Wang Y, Hanley M, Talbot D, Miao Z, Schall TJ (March 2000). "Cutting edge: identification of a novel chemokine receptor that binds dendritic cell- and T cell-active chemokines including ELC, SLC, and TECK". Journal of Immunology. 164 (6): 2851–2856. doi:10.4049/jimmunol.164.6.2851. PMID 10706668.

- Annunziato F, Romagnani P, Cosmi L, Beltrame C, Steiner BH, Lazzeri E, et al. (July 2000). "Macrophage-derived chemokine and EBI1-ligand chemokine attract human thymocytes in different stage of development and are produced by distinct subsets of medullary epithelial cells: possible implications for negative selection". Journal of Immunology. 165 (1): 238–246. doi:10.4049/jimmunol.165.1.238. PMID 10861057.

- Hirose J, Kawashima H, Yoshie O, Tashiro K, Miyasaka M (February 2001). "Versican interacts with chemokines and modulates cellular responses". The Journal of Biological Chemistry. 276 (7): 5228–5234. doi:10.1074/jbc.M007542200. PMID 11083865.

- Till KJ, Lin K, Zuzel M, Cawley JC (April 2002). "The chemokine receptor CCR7 and alpha4 integrin are important for migration of chronic lymphocytic leukemia cells into lymph nodes". Blood. 99 (8): 2977–2984. doi:10.1182/blood.V99.8.2977. PMID 11929789.

- Grant AJ, Goddard S, Ahmed-Choudhury J, Reynolds G, Jackson DG, Briskin M, et al. (April 2002). "Hepatic expression of secondary lymphoid chemokine (CCL21) promotes the development of portal-associated lymphoid tissue in chronic inflammatory liver disease". The American Journal of Pathology. 160 (4): 1445–1455. doi:10.1016/S0002-9440(10)62570-9. PMC 1867219. PMID 11943728.

- Banas B, Wörnle M, Berger T, Nelson PJ, Cohen CD, Kretzler M, et al. (May 2002). "Roles of SLC/CCL21 and CCR7 in human kidney for mesangial proliferation, migration, apoptosis, and tissue homeostasis". Journal of Immunology. 168 (9): 4301–4307. doi:10.4049/jimmunol.168.9.4301. PMID 11970971.

- Christopherson KW, Hood AF, Travers JB, Ramsey H, Hromas RA (February 2003). "Endothelial induction of the T-cell chemokine CCL21 in T-cell autoimmune diseases". Blood. 101 (3): 801–806. doi:10.1182/blood-2002-05-1586. PMID 12393410.

- Stein JV, Soriano SF, M'rini C, Nombela-Arrieta C, de Buitrago GG, Rodríguez-Frade JM, et al. (January 2003). "CCR7-mediated physiological lymphocyte homing involves activation of a tyrosine kinase pathway". Blood. 101 (1): 38–44. doi:10.1182/blood-2002-03-0841. PMID 12393730.

- Wolf M, Clark-Lewis I, Buri C, Langen H, Lis M, Mazzucchelli L (April 2003). "Cathepsin D specifically cleaves the chemokines macrophage inflammatory protein-1 alpha, macrophage inflammatory protein-1 beta, and SLC that are expressed in human breast cancer". The American Journal of Pathology. 162 (4): 1183–1190. doi:10.1016/S0002-9440(10)63914-4. PMC 1851240. PMID 12651610.

- Weninger W, Carlsen HS, Goodarzi M, Moazed F, Crowley MA, Baekkevold ES, et al. (May 2003). "Naive T cell recruitment to nonlymphoid tissues: a role for endothelium-expressed CC chemokine ligand 21 in autoimmune disease and lymphoid neogenesis". Journal of Immunology. 170 (9): 4638–4648. doi:10.4049/jimmunol.170.9.4638. PMID 12707342.

- Nagakubo D, Murai T, Tanaka T, Usui T, Matsumoto M, Sekiguchi K, Miyasaka M (July 2003). "A high endothelial venule secretory protein, mac25/angiomodulin, interacts with multiple high endothelial venule-associated molecules including chemokines". Journal of Immunology. 171 (2): 553–561. doi:10.4049/jimmunol.171.2.553. PMID 12847218.